Gemini 3 Solves Handwriting Recognition and it’s a Bitter Lesson

Testing shows that Gemini 3 has effectively solved handwriting on English texts, one of the oldest problems in AI, achieving expert human levels of performance.

In the autumn of 1968, University of Manitoba Professor R.S. Morgan was optimistic that computers would soon be able to read human text instead of punch cards. “Many humanities scholars are eagerly awaiting the day when they can get their computers to scan a book,” he wrote in a new journal called Computers and the Humanities. Hopefully, he said, it would be as simple as shovelling the text “into the maw of the machine”, leaving the computer to sort out the technical bits. Morgan was an archaeologist and a computer scientist; as early as 1966, he dreamed of getting computers to read and analyze ancient Minoan hieroglyphs.[1]

Morgan was working at the height of the so-called Golden Age of AI when many problems, like computer vision, appeared to have simple solutions. After all, he had just seen the IBM 1287 firsthand and it could read 10 digits and five letters of the alphabet, provided they were written in special boxes on cards. This was proof of concept. “It can read any printed, typewritten or handwritten numbers,” he explained, excitedly, “and it is at this point that we have a glimpse of what humanists are waiting for, an optical reader which will read any font…A machine that combines cheapness” with accuracy. If this transpired, Morgan could see that a whole host of knowledge-work professions would be radically changed. He was a bit early.

Sixty years after the launch of the IBM 1287, Gemini 3 Pro has solved handwriting transcription, scoring at levels previously reserved for expert human typists. In our tests, it did so reliably and without hallucinations. As we’ll see, the errors it does make are different than those that humans make and are largely centred on fixing punctuation, capitalization, and spelling errors in the original. That this level of accuracy was achieved by a generalist tool like an LLM rather than specialized systems will appear remarkable and surprising to many, but was entirely predictable. As a result, historical work is about to change forever.

HTR has a Long Tail

Like many problems in AI, although HTR was easy to prototype, it proved exceedingly difficult to solve. The issue is combinatorial explosion: there are only 26 letters in the Western alphabet, but put together into words and sentences, the shapes used to create them can be drawn in nearly infinite ways. If you try to devise rules and methods to handle all the various combinations of letters, the rules themselves become nearly infinite, often contradictory, and thus impossible to articulate. AI researchers concluded early on that text could never just be “shovelled” into a machine. Instead, they tried to break the problem into manageable pieces.

A whole field evolved over many decades in which people worked on developing specialized systems that carefully segmented documents, identified specific elements on the page, and then recognized the text with specially trained models, fine-tuned by end-users to achieve optimal accuracy. This reduced combinatorial explosion to manageable levels, but it also meant that transcripts would always have significant levels of errors that would have to be manually corrected. It sped up transcription, but it was certainly not what Morgan had imagined.

Today, the best-known of the systems to emerge from this tradition, Transkribus, achieves Character Error Rates (CER) of 8% and Word Error Rates (WER) of 20% on raw English language documents, without finetuning. If users provide dozens of pages of sample transcriptions, it can achieve CERs of around 3% on handwritten texts, with word error rates of around 6-8%, although results vary widely depending on the handwriting and condition of the document.

What really matters is how this equates with human accuracy on transcription tasks, which varies significantly with experience. One recent 2022 study of 1,301 University students found CERs of around 12-21% when amateur subjects were asked to transcribe typewritten texts. Another study of professional typists from in the 1980s compared results from both trainees and those with many years of experience. It found that the more experienced typists achieved an average CER of 0.95% (ranging from 0.4% to 1.9%) while novices averaged 3.2%. One of the very best human typists is reported to have achieved a CER of around 0.23%.

All of the above studies deal with typewritten sources, so we must assume that these figures represent an absolute floor for human performance: error rates on handwritten records will always be higher, probably significantly so, and vary according to the quality of the writing and the documents themselves. It is also important to consider what these seemingly small differences would mean in practice.

A 3% error rate equates to about 3-4 errors per sentence, making the document a first draft at best but also fundamentally untrustworthy. An error rate of 1% means around one error per sentence, readable but still in need of significant and close proof reading. At 0.5%, a document becomes both usable and trustworthy with around 1-2 characters wrong on each page. If one planned to publish such a document, careful proof reading would still be necessary, but it would be more akin to copy-editing than re-interpretation.

And Now Gemini Solves HTR

Sixty years and several AI winters after IBM first introduced the 1287, Gemini 3 Pro has solved HTR on English language texts. By “solved” I don’t mean absolute perfection, because that’s impossible with handwriting, but that Gemini 3 consistently produces text with error rates comparable to the very best humans.

Over the past few weeks, Dr. Lianne Leddy and I have tested Gemini 3 on our set of 50 English language, 18th and 19th century handwritten documents we’ve been using over the past two years. We chose these documents to represent the range of handwriting types, document styles, and image resolutions we typically work with, containing letters, legal documents, meeting transcriptions, minutes, memorandums, and journal entries from North America and Britain. We also tried to chose documents that we’re reasonably confident aren’t in the model’s training data (although we can’t be sure because that information is not public).

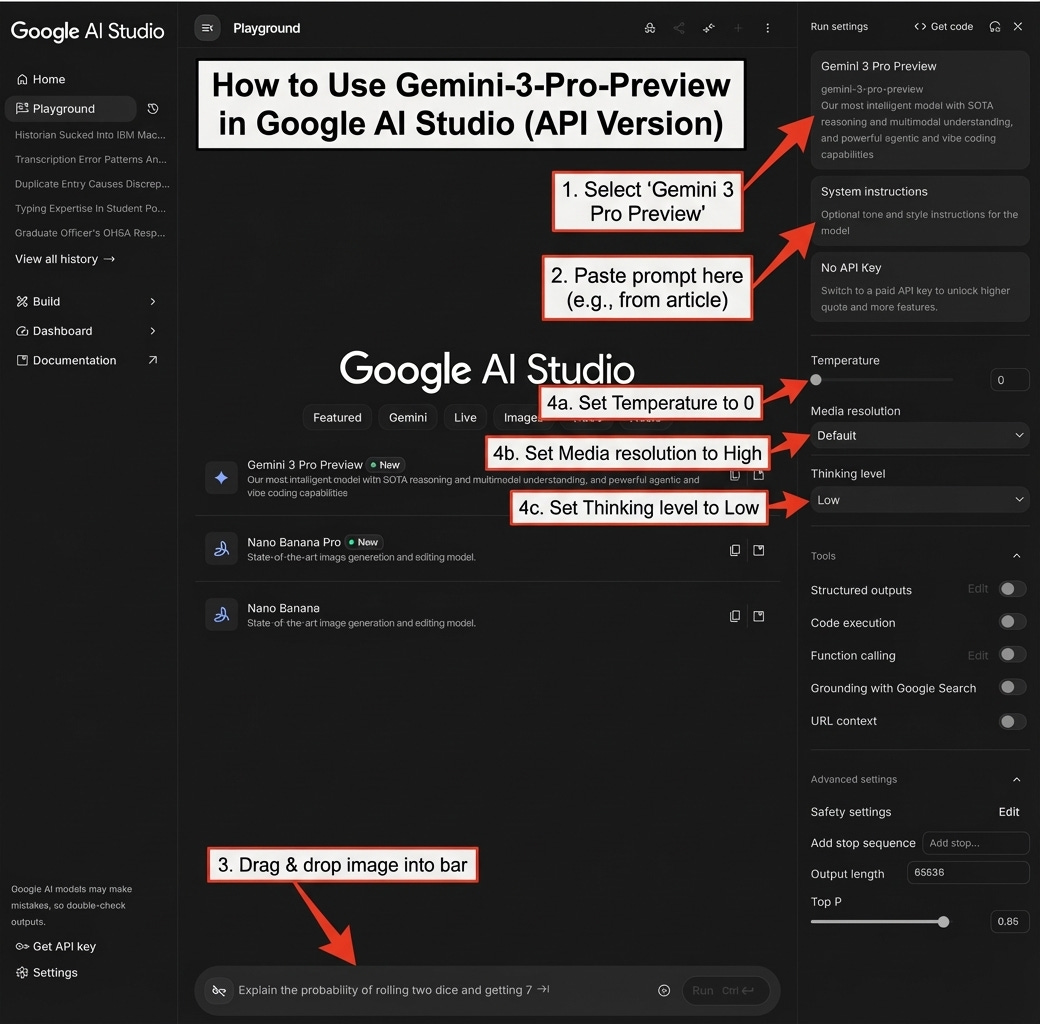

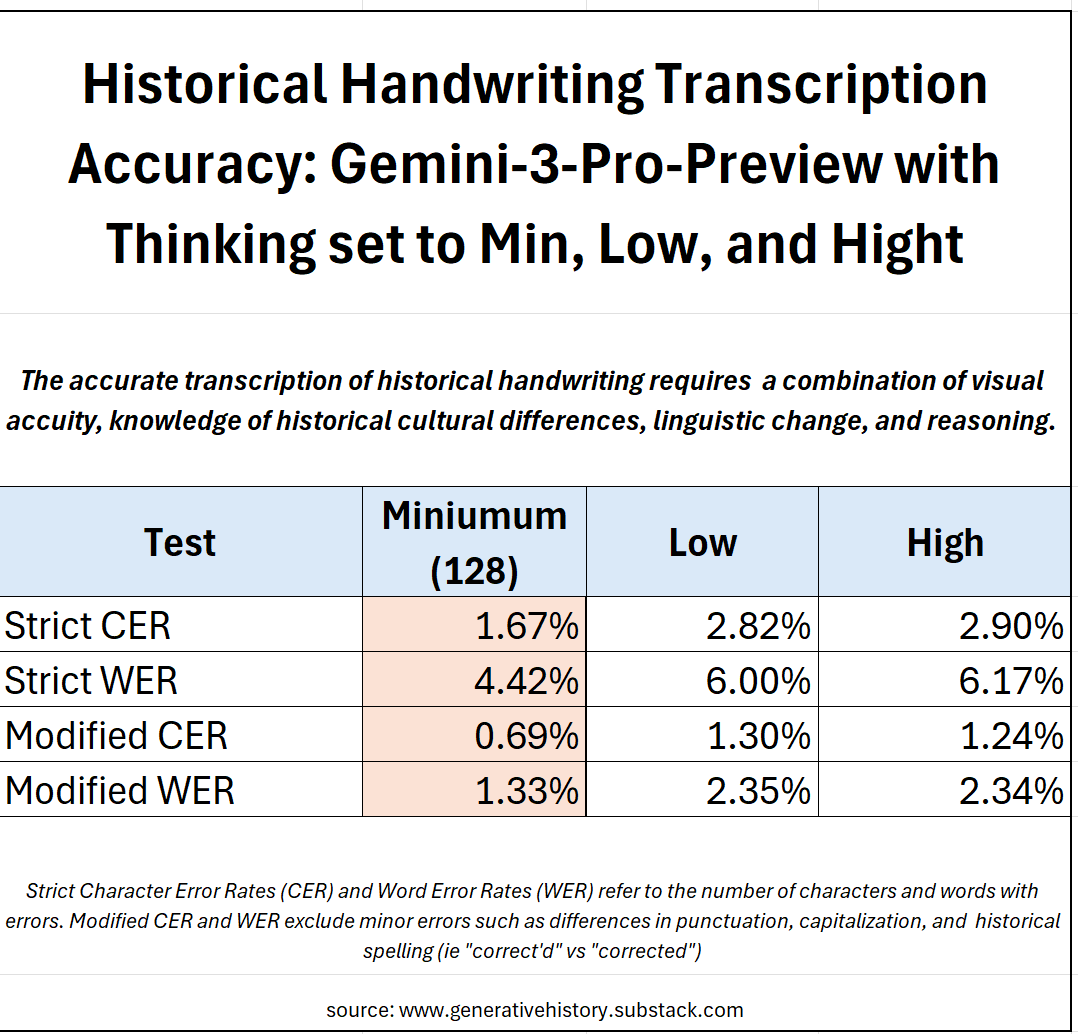

We tested the Gemini-3-Pro-Preview model via the API using a version of our Transcription Pearl software set-up for benchmarking. For each test we ran the set of 50 documents (10,000 words) through the model 10 times each—so 500 documents, 100,000 words per test. We obtained the best performance with temperature (how variable the model’s outputs are) set to 0, media resolution to high (the best image quality), and the thinking level at the minimum of 128. This may sound counter intuitive, but I’ll explain more below. We also normalized the text by removing extra whitespace, standardizing quotation marks to straight rather than curly forms, and removing special formatting like underlines, superscript, etc. Nevertheless, we expected the model to correctly handle insertions and strikeouts as well as marginalia, placing them as indicated by the author.

Our prompt was as follows:

Your task is to accurately transcribe handwritten historical documents, minimizing the CER and WER. Work character by character, word by word, line by line, transcribing the text exactly as it appears on the page. To maintain the authenticity of the historical text, retain spelling errors, grammar, syntax, capitalization, and punctuation as well as line breaks. Transcribe all the text on the page including headers, footers, marginalia, insertions, page numbers, etc. If insertions or marginalia are present, insert them where indicated by the author (as applicable). Exclude archival stamps and document references from your transcription. In your final response write Transcription: followed only by your transcription.

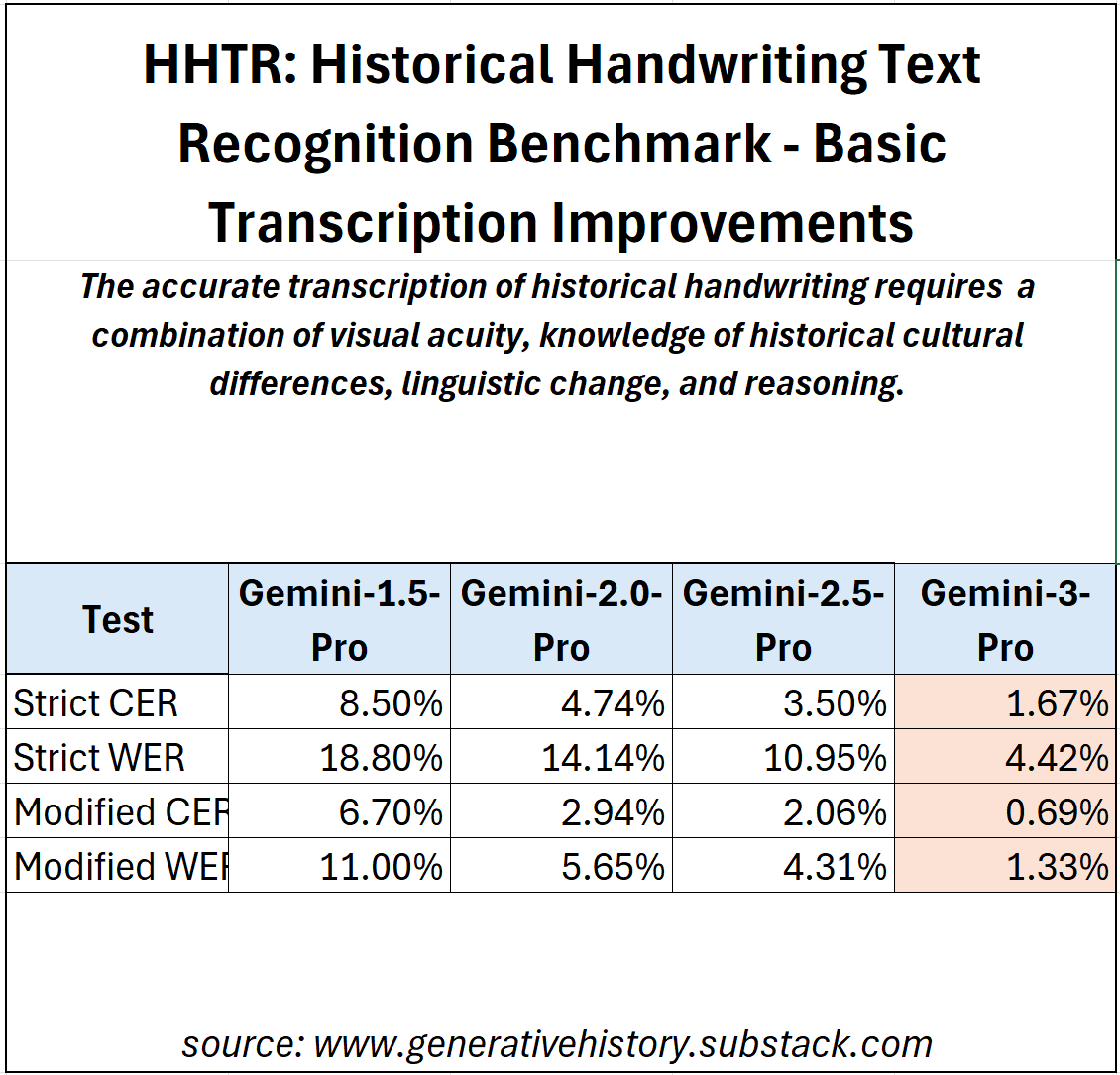

On our strictest tests, Gemini 3 achieved a CER of 1.67% and a WER of 4.42%. On these tests, any difference between the ground truth and test texts counts as an error. WER is thus almost always a bit more than double the CER because if a single character in a word is wrong, including leading or trailing punctuation like commas, single quotes vs double quotes, etc, the whole word is marked as an error. On this measure, Gemini 3 performs nearly 50% better than the best, fine-tuned specialized models and achieved performance comparable to an early career, professional human typist.

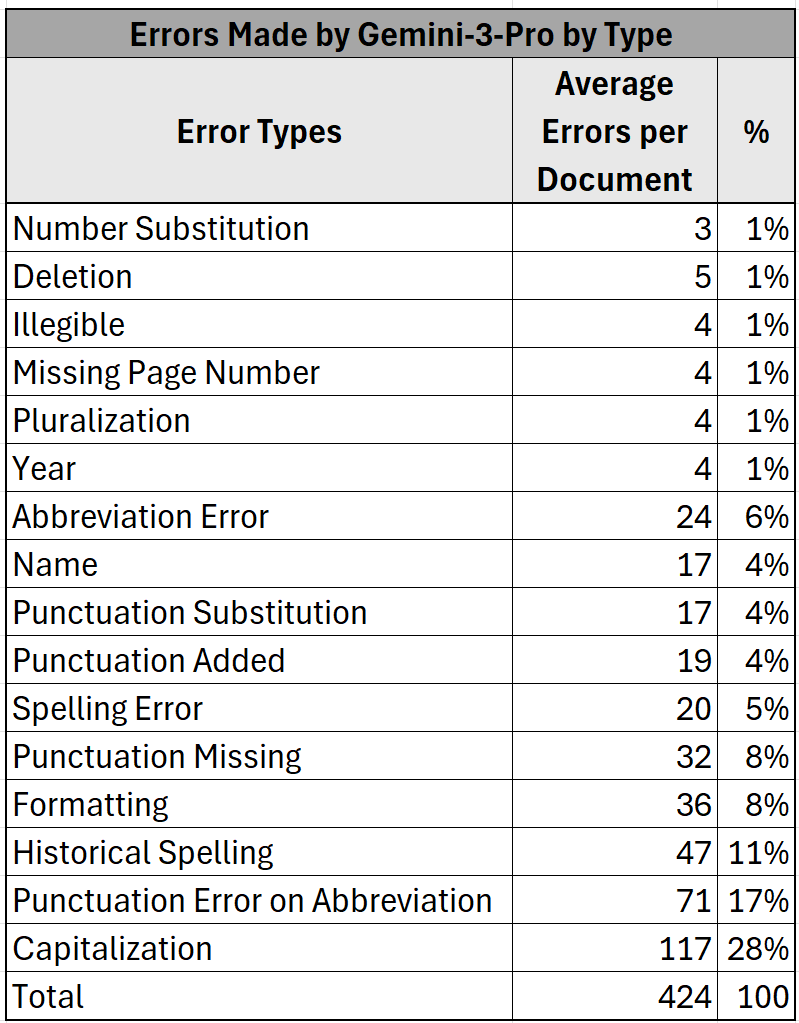

Yet many of the errors which Gemini makes are, for all practical purposes, pseudo-errors in that they often pertain to ambiguous text, formatting inconsistencies, truly illegible text, or other errors that do not change the actual spelling of the word (ie punctuation and capitalization errors). As seen in Figure 2, 76% of all the errors made by Gemini fall into one of these categories, so things like mistaking an uppercase S for a lowercase s, or a comma with a period. When we exclude these types of errors, Gemini achieves an average CER of 0.69% and an average WER of 1.33%. This makes these documents highly readable and trustworthy, but they would require good copyediting before publication.

If you look at Figure 1, this is a significant improvement over previous DeepMind models, with the latest results representing an improvement of around 65% from the model released last winter which, itself, had improved by about the same margin from Gemini 1.5.

Google is also well ahead of the competition on this benchmark. Just this week, Anthropic released a new version of its Claude Opus model (4.5) and on the same tests, Opus-4.5 achieves a strict CER of 4.28% and WER of 9.03% and a modifed CER of 2.53% and WER of 4.38%. This shows a massive improvement over Sonnet-3.7 (Strict: CER 10.45%; WER 15.65% and Modified: CER 7.47% and WER 9.88%) but still falls far short of Gemini. Meanwhile OpenAI, which has always struggled on handwriting after debuting the first model that could actually read historical documents, achieves a strict CER of 16.81% and WER of 23.51% and modified scores of 11.9% and 16.09% respectively.

Understanding LLM Errors

Many will be surprised to learn that Gemini 3’s performance is remarkably consistent. When the temperature is set to 0, Gemini transcribes the same document image almost exactly the same way each time. From a technical point of view, this is to be expected, but it does not follow popular narratives which suggest that LLMs don’t provide repeatable outputs.

But we also need to be conscious to proof-read LLM transcriptions differently because Gemini makes very different types of errors than humans. Studies show that mechanical errors are by far the most common type of human error on these tasks, that is errors that come from hitting adjacent keys, a key in the wrong row, or using the wrong hand, accounting for 68% of all errors (Grudin, 122). Psychologists think the remaining mistakes come from our inner monologue as we typically substitute phonetic sounds (meaning we substitute a different vowel) or make transpositional errors, accidentally reordering letters when our minds get ahead of our fingers.

Gemini’s most dominant errors reflect its architecture as neural-network designed to predict the next token: 61% of its errors involve making changes to the transcription which are more statistically probable than what was on the original page, according to the patterns it learned from its training data. This means it tries to standardize capitalization, punctuation, and spelling. For example, it will never misspell a word, but it sometimes will correct the spelling of a misspelled word in the text. The rest relate to things that lack predictability and require visual acuity. Gemini will sometimes get names and numbers wrong, accounting for 6% of its errors, because these are not inherently predictable: the model does not know whether the author meant 1765 or 1766…unless the document comes from a journal and it can follow a sequence of numbers. The remainder tend to relate to formatting, that is question of how one represents paper conventions on the screen.

The most remarkable thing, though, is that Gemini is so often able to push past the ruts created in training that want to steer it towards correcting historical spelling errors and capitalizations. Most of the time—99% in fact—it succeeds.

Hallucinations were entirely absent. By hallucinations, I mean insertions or replacements that are not derived from the text. There were a few genuine errors, 20 of 10,040 to be exact, but I would count these as spelling errors: in very on, these vs those, where vs were, etc. Your experience may be different, but this represents 10 full runs across 50 pages. Whatever the true rate, it is vanishingly low.

The final point to consider is cost. Gemini 3 costs $2.00 per million input tokens and $12.00 per million output tokens. In practice, after you convert high quality images to tokens, this works out to around 1,700 input tokens and 500 output tokens per page, or around 1 cent USD per page. At those rates, you can transcribe 5000 pages of text for $50.00.

Try it Yourself

If you are looking to try this yourself, it is very important to understand that we used the API, because the version of the Gemini model available on the Gemini App and website is VERY different. But don’t worry it is easy to try the better model! If you want to try out the API, don’t be scared: you can do so for free and without learning how to program in python by visiting Google’s AI Studio.

On the website, select Gemini-3-Pro-Preview in the right-hand pane and copy and paste the prompt we used above into the System Instructions, then drag and drop your image into the bar at the bottom of the screen. To get the best performance, set the temperature to 0, media resolution to high, and thinking level to low (you can’t set it any lower without using the actual API via code).

Thinking and Visual Accuracy

It is interesting that all of the so-called reasoning models perform best on transcription with “thinking” set to the minimum. This is true of OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google models. If we look at Figure 5, you’ll see that while there is not much difference between the scores for the model with thinking set to low or high, when it is set to the minimum of 128, the score are up to 75% better. This may sound especially surprising because, as I’ve said previously, the final mile in transcription accuracy seems to require improved reasoning.

The first think to understand that the “reasoning” we tweek with these settings is not actually the intelligence of the model, but rather it is told to spend additional tokens ruminating on a problem. What this effectively means is that it operates in a loop, going over and over elements of the problem and testing different answers before it makes a final response. On many problems, such as those involving math and logic this is highly useful, but there is some good evidence that for those that require a combination of visual acuity and logic, the snap judgements made by the base models are better.

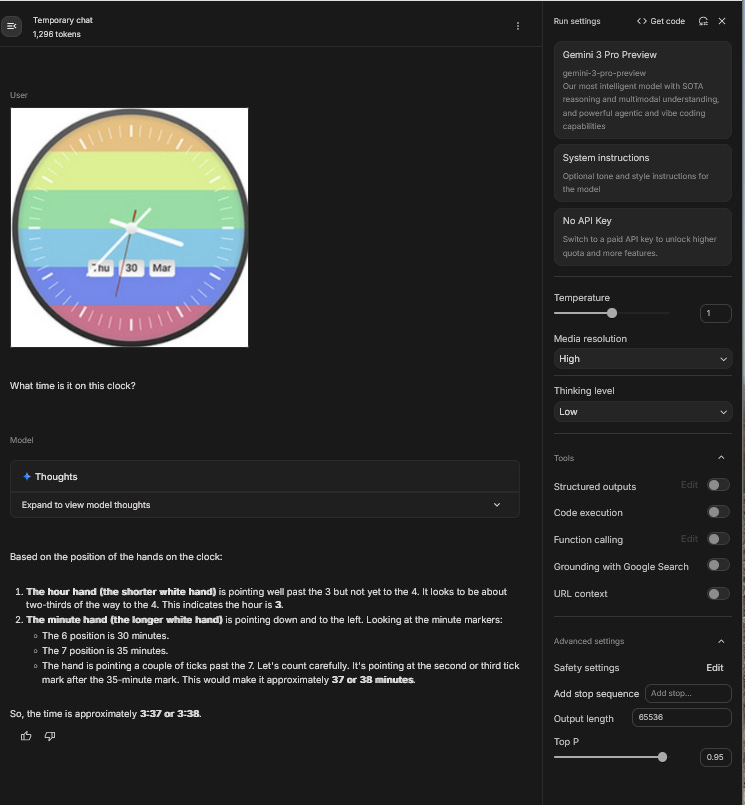

One way that I found to test this institution is a simple visual trick that people were posting to X. In the figure below, you send this trick image of a clock to the model and ask it to tell you the time. Historically, LLMs have been very bad at these sorts of visual problems because the colours and lines confuse the model and the clock does not actually look at all like the clocks it’s seen in its training.

With lots of users reporting that it was failing, I was curious and tried it out myself. What I found was, that when reasoning was set on low it would get the correct answer 95% of the time. When the reasoning was set to high, it almost always failed. The reason became clear when I looked at the model’s reasoning traces—the summaries of the chain of thought process we initiate with the reasoning/thinking setting. The model almost always got the correct time, usually down to the second, within the first couple of seconds but if it is encouraged to keep thinking about the problem for longer, as is the case when thinking is set to high, it starts to second guess itself and gradually assumes that big hand is, in fact, the short hand. I think we are seeing something similar with transcription.

Fruits of the Bitter Lesson

There are of course some important caveats on what I’ve written above as we tried the model on a small number of bespoke, English language documents. While I am now confident that the model is good enough to trust to transcribe most of the texts I’m likely to work with, it may not perform as well for you.

But this is where we need to absorb the implications of what Richard Sutton called “the Bitter Lesson”. Sutton is a highly respected AI pioneer, but is not that well known outside of tech circles. In 2019, he wrote a short essay of the same name that has garnered countless citations and become something of a mantra in the AI community. Sutton wrote: “The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.” What he meant, was, given that compute increases exponentially over time, generalized models—which are inherently more flexible—will eventually beat specialized models on every task. This may sound counter intuitive, but it is, in essence, the basis of the concept of scaling and why bigger models suddenly seem to do things that smaller models cannot.

If we look at how Gemini has improved on English language transcription over time (Figure 5), scaling suggests that you should expect to see similar progress on the documents from your own field over the next months and years. Consider that eighteen months ago, Gemini 1.5 was still getting about 1/5 words wrong, producing what was basically nonsense. Today it is nearly perfect.

Improvements won’t be evenly distributed—remember Ethan Mollick’s jagged frontier argument—but you should expect that in the next few years, it will be possible to transcribe documents in whatever language you work in with similar levels of accuracy. In software, developers are getting used to the idea that you don’t build for the models we have today, but the models you can predict we’ll have in 6-12 months. Historians should plan the same way.

So nearly sixty years after R.S. Morgan began to contemplate a world in which it would be cheap and easy for computers to read human text, it is indeed possible to just shove it into the “maw of the machine” and let the computer sort it out. That we got here not by symbolic logic and rules based systems, but general neural networks will indeed be a bitter lesson for the HTR community to swollow. And I get that.

For the historical community, as we gradually become accustomed to this new reality, it will radically alter how historians, genealogists, archivists, governments, and researchers relate to our documentary past. It’s also a harbinger of the larger changes in our relationship with information that are now certain to come from scaling.

[1] “Notes”, Newsletter of Computer Archaeology, 2 (1966): 11

Gemini is my go-to for handwritten documents. I find it the best of the options. However, I have identified two issues not on your errors list. First, it can totally skip lines in a document, and second it can substitute words. I do not see those in your chart. It also does a marginal job on things written in the margins or inserted between lines. It is still way better than doing it yourself!

Hi Mark, great post as always! I've been experimenting with AI Studio and I think in the end the performance has nothing to do with language, solely with how hard the hands are. It does extraordinarily well with clear French, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese handwriting, for instance. I therefore assume the main problem is computer vision, not the underlying language. So I'm not so sure LLMs will surpass Transkribus anytime soon for harder hands, but I might be wrong, as I've underestimated LLMs' transcription capabitilies before!